The animal we commonly recognise as a sea jelly (the medusa) is just one part of a jelly’s complicated life cycle. The medusae are the sexual stage of the life cycle. Some species of sea jelly have separate male and female medusae but other species are hermaphroditic (the one individual has both male and female reproductive organs). The medusae produce eggs and sperm and, once fertilised, form microscopic, torpedo-like larvae. The larvae swim to the sea floor where they attach to something hard, such as a rock or shell and change form (metamorphose) into a polyp. The polyps are tiny – just one or two millimetres tall, and so are very difficult to find. We know from experiments in the laboratory that polyps can clone themselves by budding. Sometimes a single polyp may produce dozens of clones. When conditions are favourable juvenile sea jellies (ephyrae) begin to form on top of the polyp. The polyps of some species form just one ephyra at a time but some species, such as the moon jelly, Aurelia aurita, may produce dozens of ephyrae from a single polyp. Once they break free from the polyp, the ephyrae swim away and grow into medusae.

The life cycle of most sea jellies follows one direction – medusa to larva to polyp to ephyra and back to medusa. Some cnidarians like the Mauve stinger, Pelagia noctiluca, lack the polyp stage. A few remarkable species are even able to reverse parts of their life cycle. For example, medusae of the hydrozoan jelly Turritopsis may revert back to the polyp form when the medusa is sick or damaged. Turritopsis has become known as the ‘immortal jellyfish’ because, by transitioning between the medusa and polyp form, in theory it may never die!

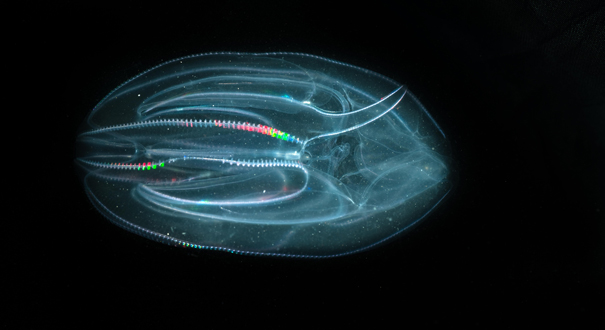

Comb jellies differ to the majority of cnidarian jellies because they do not have a polyp stage in their life cycle. Most comb jellies are hermaphrodites and many can self-fertilise, which may be an advantage when comb jellies are scarce and the chances of encountering an individual of the opposite sex are low. Once fertilised, the eggs of comb jellies develop into a larva that grows directly into another ctenophore. The entire life cycle of some comb jellies can be completed in as little as two weeks!